Leasing is the mechanism used between applications to give access to resources over a period of time in an agreed manner

Leases are requested for a period of time.

In distributed applications, there may be partial failures of the network

or of components on this network. Leasing is a way for components to

register that they are alive, but for them to be ``timed out'' if they

have failed, are unreachable, etc.

In Jini, one use of leasing

is for a service to request that a copy be kept on a lookup service

for a certain length of time for

delivery to clients on request. The service requests a time in the

ServiceRegistrar's method register().

Two special values of the time are

Lease.ANY - the service lets the lookup

service decide on the time

Lease.FOREVER - the request is for a lease that never expires

The lookup service acts as the granter of the lease,

and decides how long it will actually create the lease for.

(The lookup service from Sun typically sets the lease time as

only five minutes.)

Once it has done that, it will attempt to ensure that the request

is honoured for that period of time. The lease is returned to the

service, and is accessible through the method getLease()

of the ServiceRegistration object. These objects are shown

in figure 8.1

ServiceRegistration reg = registrar.register();

Lease lease = reg.getLease();

The principal methods

of the Lease object are

package net.jini.core;

public interface Lease {

void cancel() throws

UnknownLeaseException,

java.rmi.RemoteException;

long getExpiration();

void renew(long duration) throws

LeaseDeniedException,

UnknownLeaseException,

java.rmi.RemoteException;

}

getExpiration() is the time in milliseconds

since the beginning of the epoch

(the same as in System.currentTimeMillis()).

To find the amount of time still remaining from the present, the current time

can be subtracted from this:

long duration = lease.getExpiration() - System.currentTimeMillis();

A service can cancel its lease by using cancel().

The lease communicates

back to the lease management system on the lookup service which

cancels storage of the service.

When a lease expires, it does so silently. That is, the lease granter

(the lookup service) will not inform the lease holder (the service)

that it has expired.

While it might seem nice to get warning of a lease expiring so that it

can be renewed, this would have to be in advance of

the expiration (``I'm just about to expire, please renew me quickly!'')

and this would probably be impractical.

Instead, it is upto the service to call renew()

before the lease expires if it wishes the lease to continue.

Jini supplies a class LeaseRenewalManager that looks after

the process of calling renew() at suitable times.

package net.jini.lease;

public Class LeaseRenewalManager {

public LeaseRenewalManager();

public LeaseRenewalManager(Lease lease,

long expiration,

LeaseListener listener);

public void renewFor(Lease lease, long duration,

LeaseListener listener);

public void renewUntil(Lease lease,

long expiration,

LeaseListener listener);

// etc

}

renewFor() or renewUntil().

The time requested in these is in milliseconds.

The expiration time is since the epoch, whereas the

duration time is from now.

Generally leases will be renewed and the manager will function

quietly. However, the lookup service may decide not to renew a

lease and will cause an exception to be thrown. This will be caught

by the renewal manager and will cause the listener's notify()

method to be called with a LeaseRenewalEvent as

parameter. This will allow the application to take corrective

action if its lease is denied.

The listener may be null.

All of the above discussion was from the side of a client that receives a lease, and has to manage it. The converse of this is the agent that grants leases and has to manage things from its side. This section contains more advanced material which can be skipped for now: it is not needed until the chapter on ``Remote Events''. An example of use is given in the chapter on ``More Complex Examples''.

A lease can be granted for almost any remote service, any one where one object wants to maintain information about another one which is not within the same virtual machine. Being remote, there are the added partial failure modes such as network crash, remote service crash, timeouts and so on. An object will want the remote service to keep ``pinging'' it periodically to say that it is still alive and wants the information kept. Without this periodic assurance, the object may conclude that the remote service has vanished or is somehow unreachable, and it should discard the information about it.

Leases are a very general mechanism for one service to have confidence in the existence of the other for a limited period. Being general, it allows a great deal of flexibility in use. Because of the possible variety of services, some parts of the Jini lease mechanisms cannot be given totally, and must be left as interfaces for applications to fill in. The generality means that all the details are not filled in for you, as your own requirements cannot be completely predicted in advance.

A lease is given as an interface

package net.jini.core.lease;

import java.rmi.RemoteException;

public interface Lease {

long FOREVER;

long ANY;

long getExpiration();

void cancel() throws UnknownLeaseException, RemoteException;

void renew(long duration)

throws LeaseDeniedException, UnknownLeaseException, RemoteException;

void setSerialFormat(int format);

int getSerialFormat();

LeaseMap createLeaseMap(long duration);

boolean canBatch(Lease lease);

}

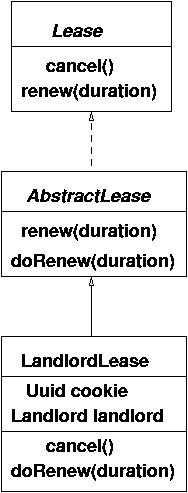

AbstractLease with

subclass a LandlordLease which in turn has a subclass

ConstrainableLandlordLease

A main issue in implementing a particular lease class lies in setting a policy for handling the initial request for a lease period, and in deciding what to do when a renewal request comes in. Some simple possibilities are

Always grant the requested time

Ignore the requested time and always grant a fixed time

There are other issues, though. Any particular lease will need a time-out mechanism. A group of leases can be managed together, and this can reduce the amount of overhead of managing individual leases.

An abstract lease gives a basic implementation of a lease, that can almost be used for simple leases.

package com.sun.jini.lease;

public abstract class AbstractLease implements Lease, java.io.Serializable {

protected AbstractLease(long expiration);

public long getExpiration();

public int getSerialFormat();

public void setSerialFormat(int format);

public void renew(long duration);

protected abstract long doRenew(long duration);

}

Lease interface, with three provisos: firstly, the constructor

is protected,

so that constructing a lease with a specified duration

is devolved to a subclass. This means that lease duration policy must be

set by this subclass. Secondly, the renew() method calls

into the abstract doRenew() method, again to force a

subclass to implement a renewal policy. Thirdly,

it does not implement the methods

cancel() and createLeaseMap(),

so that these must also be left to a subclass.

So this class implements the easy things, and leaves all matters of

policy to concrete subclasses.

Section on landlord package and later stuff removed for now till I get it properly sorted out

The ``landlord'' is a package to allow more complex leasing systems

to be built. It is not part of the Jini specification, but is supplied

as a set of classes and interfaces.

(Warning: this is part of the com.sun.jini

package, which has changed from Jini 1.0. For Jini 1.0, see earlier versions

of this tutorial)

The set is not complete in itself -

some parts are left as interfaces, and need to have class implementations.

These will be supplied by a particular application.

A landlord looks after a set of leases.

Leases are indentified to the landlord by a ``cookie'',

which is a unique identifier (Uuid) for each lease.

A landlord does not need to create leases itelf, as it can

use a landlord lease factory to do this. (But of course it

can create them,

depending on how an implementation is done.)

When a lease wishes to

cancel or renew itself, it asks its landlord to do it. A client is unlikely

to ask the landlord directly, as it will only have been given a lease, not

a landlord.

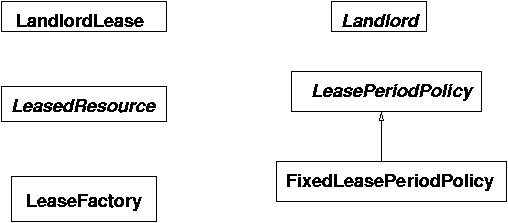

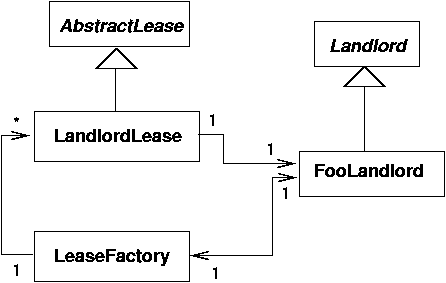

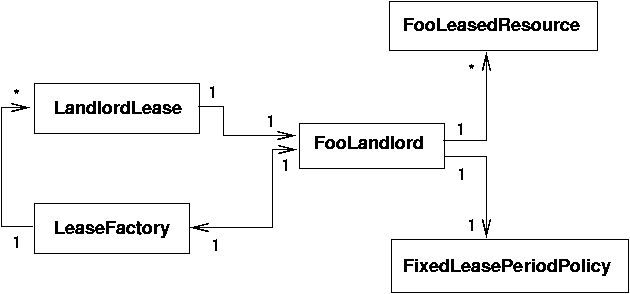

The principal classes and interfaces in the landlord

package are shown in figure 8.2 .

The interfaces assume that they will be implemented in certain ways, in that each implementation class will contain a reference to certain other interfaces. This doesn't show in the interface specifications, but can be inferred from the method calls.

For example, suppose we wish to develop a lease mechanism for a Foo

resource. We would create a FooLandlord to create and manage

leases for Foo objects. A minimal structure for this could be

renew() these are passed to the landlord for decisions.

However, when the renew() request to the landlord does

not pass in the lease, but just its uuid.

What is missing from the above simple figure is how the resource itself is dealt with, where leases end up and how decisions are made about whether or not to grant leases or renewals.

Leases are given to the client that is requesting a lease. Calls such

as renew() are remote calls to the landlord. It doesn't

need a copy of the lease, but does need some representation of it.

that is what the cookie is for: a leasor-side representation of the

lease

The resource that is being leased has a representation on the leasor.

For example, a lookup service would have the marshalled form of the

service proxy to manage. The leasor needs to have this representation

plus the lease "handle" (the cookie) and information such as lease

duration and expiration. These are given in an implementation of

the LeasedResource interface

Decisions about granting or renewing leases would need to be made

using the LeasedResource. While these could be made

by the landlord, it is cleaner to hand such a task to a separate

object concerned with such policy decisions. This is the function

of LeasePeriodPolicy objects. For example, the

FixedLeasePeriodPolicy has a simple policy

that grants lease times based on a fixed default and maximum lease

These lead to a more complex class diagram involving the resource and the policy classes:

With this as context, we shall now consider some of these classes in more detail.

The class LandlordLease extends AbstractLease.

This has private fields cookie and landlord as shown in

figure 8.5.

cancel()and doRenew()

is deferred to its landlord.

public void cancel() {

landlord.cancel(cookie);

}

protected long doRenew(long renewDuration) {

return landlord.renew(cookie, renewDuration);

}

A LeasedResource is a convenience wrapper around a

resource that includes extra information and methods for use

by landlords. It defines an interface

public interface LeasedResource {

public void setExpiration(long newExpiration);

public long getExpiration();

public Uuid getCookie();

}

An implementation will typically include the resource that is leased, plus a method of setting the cookie. For example,

/**

* FooLeasedResource.java

*/

package foolandlord;

import com.sun.jini.landlord.LeasedResource;

import net.jini.id.Uuid;

import net.jini.id.UuidFactory;

public class FooLeasedResource implements LeasedResource {

protected Uuid cookie;

protected Foo foo;

protected long expiration = 0;

public FooLeasedResource(Foo foo) {

this.foo = foo;

cookie = UuidFactory.generate();

}

public void setExpiration(long newExpiration) {

this.expiration = newExpiration;

}

public long getExpiration() {

return expiration;

}

public Uuid getCookie() {

return cookie;

}

public Foo getFoo() {

return foo;

}

} // FooLeasedResource

A lease policy is used when a lease is first granted, and when it tries

to renew itself. The time requested may be granted, modified or denied.

A lease policy is specified by the LeasePeriodPolicy interface.

package com.sun.jini.landlord;

public interface LeasePeriodPolicy {

LeasePeriodPolicy.Result grant(LeasedResource resource, long requestedDuration);

LeasePeriodPolicy.Result renew(LeasedResource resource, long requestedDuration);

}

An implementation of this policy

is given by the FixedLeasePeriodPolicy.

The constructor takes maximum and default lease values.

It uses these to grant and renew leases.

The Landlord is the final interface in the package that we need

for a basic landlord system. Other classes and interfaces,

such as LeaseMap are for handling of leases in ``batches'',

and will not be dealt with here. The Landlord interface is

package com.sun.jini.lease.landlord;

public interface Landlord extends Remote {

public long renew(Uuid cookie, long extension)

throws LeaseDeniedException, UnknownLeaseException, RemoteException;

public void cancel(Uuid cookie)

throws UnknownLeaseException, RemoteException;

public RenewResults renewAll(Object[] cookies, long[] durations)

throws RemoteException;

public Map cancelAll(Uuid[] cookies)

throws RemoteException;

}

renew() and cancel() methods are usually called

from the renew() and cancel() methods of a particular

lease. An implementation of Landlord such as FooLandlord

will probably have a table of LeasedResource objects indexed by

the Uuid so that it can work out which resource the request is about.

The landlord won't make decisions itself about renewals.

The renew() method needs to use a policy object to ask

for renewal. In the FooManager implementation it uses a

FixedLeasePeriodPolicy

There must be a method to ask for a new lease for a resource. This is not

specified by the landlord package. This request will probably be made on

the lease granting side and this should have access to the landlord object,

which forms a central point for lease management. So the FooLandlord

will quite likely have a method such as

public Lease newFooLease(Foo foo, long duration);

The lease used in the landlord package is a LandlordLease.

This contains a private field, which is a reference to the landlord itself.

The lease is given to a client as a result of newFooLease(),

and this client will usually be a remote object. This will involve

serialising the lease and sending it to this remote client. While

serialising it, the landlord field will also be serialised and sent to

the client. When the client methods such as renew() are called,

the implementation of the LandlordLease will make a call

to the landlord, which by then will be remote from its origin. So the

landlord object invoked by the lease will need to be a remote object

making a remote call. In Jini 1.2 this would have been done by making

FooLandlord a subclas of UnicastRemoteObject.

In Jini 2.0 this is preferably done by explicitly exporting the landlord

to get a proxy object. In the code that follows this is done using a

BasicJeriExporter (for simplicity) but it would be better to use

a configuration.

Putting all this together for the FooLandlord class gives

/**

* FooLandlord.java

*/

package foolandlord;

import net.jini.core.lease.UnknownLeaseException;

import net.jini.core.lease.LeaseDeniedException;

import net.jini.core.lease.Lease;

import net.jini.jeri.BasicJeriExporter;

import net.jini.jeri.BasicILFactory;

import net.jini.jeri.tcp.TcpServerEndpoint;

import net.jini.export.*;

import java.rmi.Remote;

import java.rmi.RemoteException;

import java.util.Map;

import java.util.HashMap;

import net.jini.id.Uuid;

import com.sun.jini.landlord.Landlord;

import com.sun.jini.landlord.LeaseFactory;

import com.sun.jini.landlord.LeasedResource;

import com.sun.jini.landlord.FixedLeasePeriodPolicy;

import com.sun.jini.landlord.LeasePeriodPolicy;

import com.sun.jini.landlord.LeasePeriodPolicy.Result;

import com.sun.jini.landlord.Landlord.RenewResults;

import net.jini.id.UuidFactory;

public class FooLandlord implements Landlord {

private static final long MAX_LEASE = Lease.FOREVER;

private static final long DEFAULT_LEASE = 1000*60*5; // 5 minutes

private Map leasedResourceMap = new HashMap();

private LeasePeriodPolicy policy = new

FixedLeasePeriodPolicy(MAX_LEASE, DEFAULT_LEASE);

private Uuid myUuid = UuidFactory.generate();

private LeaseFactory factory;

public FooLandlord() throws java.rmi.RemoteException {

Exporter exporter = new

BasicJeriExporter(TcpServerEndpoint.getInstance(0),

new BasicILFactory());

Landlord proxy = (Landlord) exporter.export(this);

factory = new LeaseFactory(proxy, myUuid);

}

public void cancel(Uuid cookie) throws UnknownLeaseException {

if (leasedResourceMap.remove(cookie) == null) {

throw new UnknownLeaseException();

}

}

public Map cancelAll(Uuid[] cookies) {

Map failMap = new HashMap();

for (int n = 0; n < cookies.length; n++) {

try {

cancel(cookies[n]);

} catch(UnknownLeaseException e) {

failMap.put(cookies[n], e);

}

}

if (failMap.isEmpty()) {

return null;

} else {

return failMap;

}

}

public long renew(Uuid cookie,

long extension) throws LeaseDeniedException,

UnknownLeaseException {

LeasedResource resource = (LeasedResource)

leasedResourceMap.get(cookie);

LeasePeriodPolicy.Result result = null;

if (resource != null) {

result = policy.renew(resource, extension);

} else {

throw new UnknownLeaseException();

}

return result.duration;

}

public Landlord.RenewResults renewAll(Uuid[] cookies, long[] durations) {

long[] granted = new long[cookies.length];

Exception[] denied = new Exception[cookies.length];

boolean wasDenied = false;

for (int n = 0; n < cookies.length; n++) {

try {

granted[n] = renew(cookies[n], durations[n]);

} catch(UnknownLeaseException e) {

granted[n] = -1;

denied[n] = e;

wasDenied = true;

} catch(LeaseDeniedException e) {

granted[n] = -1;

denied[n] = e;

wasDenied = true;

}

}

if (wasDenied) {

return new Landlord.RenewResults(granted, denied);

} else {

return new Landlord.RenewResults(granted, null);

}

}

public LeasePeriodPolicy.Result grant(LeasedResource resource,

long requestedDuration)

throws LeaseDeniedException {

Uuid cookie = resource.getCookie();

try {

leasedResourceMap.put(cookie, resource);

} catch(Exception e) {

throw new LeaseDeniedException(e.toString());

}

return policy.grant(resource, requestedDuration);

}

public Lease newFooLease(Foo foo, long duration)

throws LeaseDeniedException {

FooLeasedResource resource = new FooLeasedResource(foo);

Uuid cookie = resource.getCookie();

// find out how long we should grant the lease for

LeasePeriodPolicy.Result result = grant(resource, duration);

long expiration = result.expiration;

resource.setExpiration(expiration);

Lease lease = factory.newLease(cookie, expiration);

return lease;

}

public static void main(String[] args) throws RemoteException,

LeaseDeniedException,

UnknownLeaseException {

// simple test harness

long DURATION = 2000; // 2 secs;

FooLandlord landlord = new FooLandlord();

Lease lease = landlord.newFooLease(new Foo(), DURATION);

long duration = lease.getExpiration() - System.currentTimeMillis();

System.out.println("Lease granted for " + duration + " msecs");

try {

Thread.sleep(1000);

} catch(InterruptedException e) {

// ignore

}

lease.renew(5000);

duration = lease.getExpiration() - System.currentTimeMillis();

System.out.println("Lease renewed for " + duration + " msecs");

lease.cancel();

System.out.println("Lease cancelled");

}

} // FooLandlord

An Ant file for this is

Leasing allows resources to be managed without complex garbage collection mechanisms.

Leases received from services can be dealt with easily using LeaseRenewalManager.

Entities that need to hand out leases can use a system such as the landlord

system to handle these leases.

If you found this chapter of value, the full book is available from APress or Amazon . There is a review of the book at Java Zone . The current edition of the book does not yet deal with Jini 2.0, but the next edition will.

This work is licensed under a

Creative Commons License, the replacement for the earlier Open Content License.

This work is licensed under a

Creative Commons License, the replacement for the earlier Open Content License.